The Uttermost Parts of the Earth

Cat’s cradle is one of the oldest games conceived by humans, originating spontaneously in indigenous cultures across the globe. It involves looped string figures being passed between two game players, hand to hand and finger to finger, often to aid in the telling of a story or the making of a significant celestial or animal configuration. In Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene, feminist scholar Donna Haraway describes string figures as necessary cooperative pattern making between humans and earth, between animals and human: hand to hand reasoning between species as they pass an object, an idea back and forth, strategizing survival on an increasingly devastated earth. In my video, Jacob’s Ladder, I practice the Jacob’s Ladder string figure [one of the most recognizable Western string figures, and often one of the first learned] that describes the staircase to heaven as seen in an ecstatic religious vision by biblical patriarch Jacob in the Book of Genesis, with string spun out of my own hair. After collecting my hair for six months, I turned into into something utilitarian- a coarse string- and with it, I remake patterns, spinning my own body, my skin, my hair, into them.

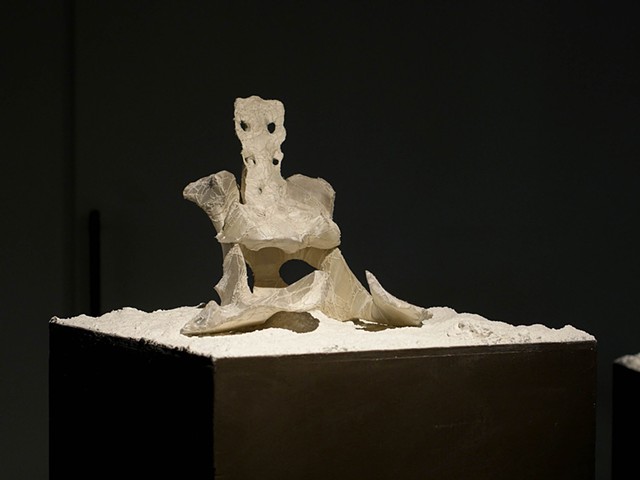

In this work, I use animal bones that have been wrapped tightly in silk or encased in the skins of other animals as both shrouds and things that have been re-skinned, remade into new animals. These new skins are tighter than the skins that would have housed them alive: they have been divested of their meat, of any fleshy barrier between skin and bone that would offer protection. These bones sit on beds of white bone ash (crushed, degelatinized, and burned animal bones used in the production of bone china). Three chicken pelts, the full skins and feathers of domestic roosters, are covered in volcanic ash (a fine blush powder created by volcanic eruptions that is then milled and used in the production of cosmetics). “Cleaving/Enfolding” is the next step in this metamorphosis of animal skin: a constructed skin of muslin (the fabric

traditionally used in pattern-making), honeycombed with thread, that bulges and sags with its own weight, growing in on itself. The skin is stuffed with chicken and partridge feathers, pierced with porcupine quills. The feathers are molting, leaving swathes of skin unfeathered and unprotected.

The title of this body of work, “The Uttermost Parts of the Earth”, is a reference to both the biblical passages describing God’s demand for far reaching dominion over both humans and nature, and the 1947 novel by Lucas Bridges of the same name that describes the total annihilation of the native peoples of Tierra del Fuego (the southernmost inhabited area of the earth) by European missionary colonizers in the late 19th century. In both cases the uttermost earth is the most far-flung, the deepest, the most essential of places, beyond the imagination of Biblical authors, beyond recognized inhabitable territory, a new and dangerous place. I imagine my work living in this place: on the furthest, most essential, most inhospitable land, where animals are enfolding in on themselves and each other, curling into each other to become something new, something unrecognizable, as the ladder from heaven unfurls from the sky.